Such precious quiet this morning at Casa Parque – on the outside.

Cool fall air floats through the dining room window, chills my toes.

But

on the inside I sense agitation. Can't get comfortable in my chair –

hard as a rock under my sitting bones. And inside my skin it feels

disorganized.

9:18. I’d planned to be up earlier. Dedicating my

weekends to the writing now. I’m behind on the book, I know, trying to

find my rhythm again after Mom’s passing. Writing is a practice, like

playing the piano. My fingers are out of shape.

I need

inspiration. From a New Yorker article? Flipping through an August

issue, this draws me in: ‘Finding the Words,’ the story of a

contemporary poet’s elegy to his dead son.

9:29. I read the first

page. Maybe it’s telling me: You’re not good enough to write this

Mexico memoir or this newly brewing essay about your mother’s life and

death. Such is the work of Wordsworth or Tennyson or the father, a

celebrated writer named Edward Hirsch.

Never even heard of him. Though further along in the article, a quote of

his speaks to me:

‘Why would I have Skokie in a poem? But you become

resigned. Your job is to write about the life you actually have.’

I

can do that. I do do that. I’m not formally trained nor particularly

sophisticated. But I’m still worthy, because I see inside, feel the

texture, cherish the truth and transcribe for others the universality of

experience. I try.

In a stanza of the poem to his late son, Gabriel, Hirsch writes:

Look closely and you will see

Almost everyone carrying bags

Of cement on their shoulders

That’s why it takes courage

To get out of bed in the morning

And climb into the day

So that’s why I read that article. Because I got out of bed this morning.

9:49. Now it’s time to write.

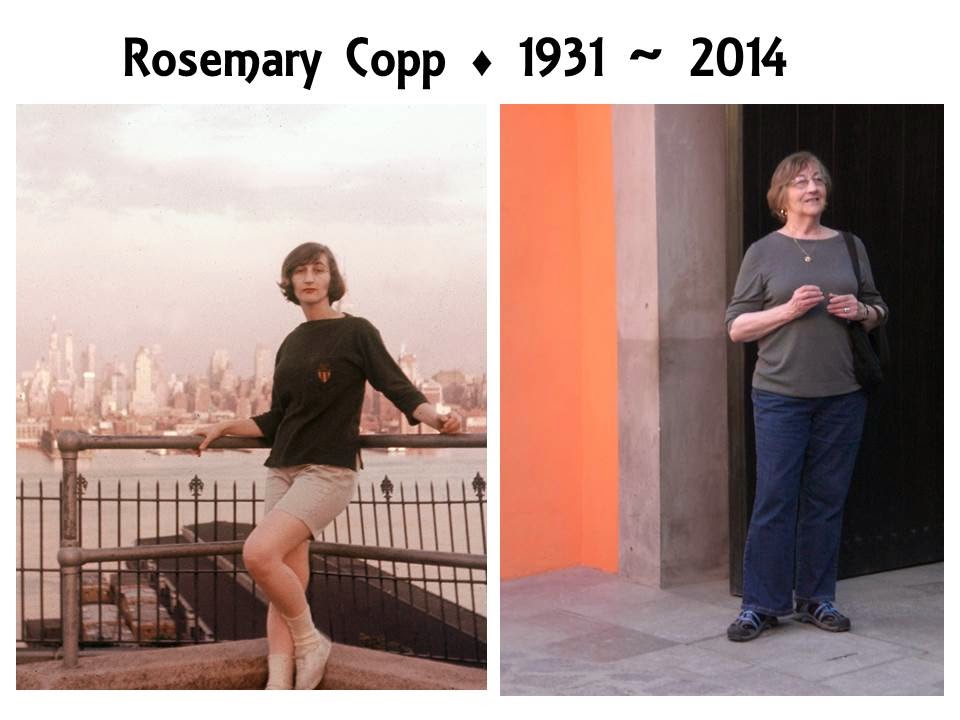

Mom’s sleeping upstairs. I hope it’s deep, rejuvenating sleep. But

how could it be. There’s nothing that could revive that broken body.

It’s already abandoned her. She tells me that at night, in bed, she has

visions of her old, strong self and she, who she is now, reaches out,

yearning to re-inhabit that body. But she cannot reach it. She awakens,

and the bloated belly that encases a cancerous liver is still there, a

nightmare from which she cannot wake-up.

Was it death that

visited me at the foot of my bed that haunted night in Mexico? I dove

out of my sleep and onto the cloaked monster screaming ‘Noooo,’ landing

on the cold cement floor of my Jimenez hovel. Awakened from the

nightmare, I crawled in the dark to my dorm fridge and found a pack of

frozen peas to put between my bruised knees. I made it through a

frightful night and went on to survive and thrive in Mexico.

But

Mom cannot dive. She can hardly sit up. She cannot walk or eat and

barely drinks, thus she cannot even eliminate. Was that the problem in

the first place, pent-up toxins in the bowel? Simply that? Her brain,

heart, lungs are perfect. She can do 20 leg lifts, she showed me

yesterday. And she has lovely toes.

She’s a model of health, proud to have never 'soaked the system,'

the only drugs she’s ever taken a light dosage blood pressure pill and

one for cholestoral. I went to the CVS today to buy her Aleve and a

stool softener. That’s the least ‘Western’ medicine can do for her.

Me,

I’m taking a G&T for the pain. Fresh mowed lawn, brilliant green

carpet laid out before me, sound of the CSX freight train tooting its

horn in the distance, the blessed wind in the trees, brushing my

shoulders. I want to cry for how beautiful this moment is.

And mom’s asleep upstairs.

You

wish you could go through this experience like this: rub your mom’s

neuropathic numb feet with the miracle cream you picked up at the

running race, comb her thin hair, scrub her bathtub and wash her bed

sheets, prepare a smoothie she forces herself to drink, out of the bendy

straw a child drinks from. 'Just two sips, mom, no three, please, for

me?'

You wish you could do this for her: reminisce quietly as BookTV blares,

about the good ole days, that illustrious trip in the station wagon to

Niagara Falls when we kids had just discovered the thrill of spitballs.

'Do you remember the one that landed in your ear!? And you, angry,

promised that was our last trip.'

My coming home with trophies, celebrating childhood triumphs in tennis,

swimming, running. Or the times I stomped up to my room, an ashamed

loser. 'But when it was a win,' Mom reminds me, I’d walk into the house

with a big smile, and she knew right away, the prize hidden behind my

back: 'Which hand?' I’d ask.

I brought one home for her

today: a wood plaque in the shape of the state of Illinois, first

place, 4-mile, Steamboat Classic, Master Female.

'You’re

still winning,' Anne, she chuckles with joy as I perch the plaque on her

dresser, upside, the flat border side of the state down.

She gazes down at my new fast Adidas. 'When my feet get better,' she says, 'I want a pair of those.'

You wish you could get past this together; then you promise yourself you’d REALLY live.

But now is what you’ve got. The luminous summer evening, the sound of a lawn mower, the tinkle of the ice cubes.

Mom’s resting in her bedroom. Should you go wake her up so she can see this?